Einstein and God

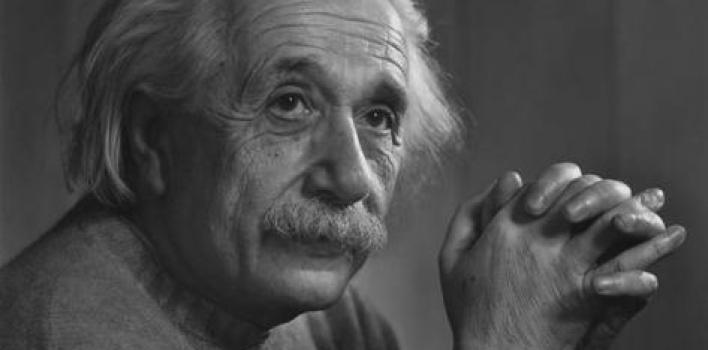

Einstein and God Itaici, Brazil – Albert Einstein (1879-1955), the most famous scientist of the 20th century was born in a non-practicing Jewish family. During childhood he had a phase of religious fervor, but at the age of 12 reading books of science convinced him that many stories of the Bible could not be true. Einstein definitely turned away from religious practice. Some militant atheists, like Richard Dawkins, include Einstein among atheist scientists. In his book The God Delusion, Dawkins writes: “Einstein sometimes invoked the name of God (and he is not the only atheistic scientist to do so), inviting misunderstanding” (p. 36 of the Brazilian edition: Deus, un delírio). And he denounces “religious apologists” who “try to claim Einstein as one of their own” (p. 39).

I feel personally implicated in Dawkins’ denounce. Indeed, years ago, I quoted Einstein’s famous phrase: “Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind.” And I added: “In his maturity, Einstein defended a ‘cosmic religiousness’ based in the presence of a superior rational power, revealed in the incomprehensible universe” (Experiência de Deus: presença e saudade. 2ª ed. revista. São Paulo: Loyola, 2002, p. 14).

To clear any doubts, the reader can look into the latest and most complete biography of Albert Einstein: Walter Isaacson’s Einstein: His life and universe (2007), translated into Portuguese by Companhia das Letras (Einstein: sua vida, seu universo. São Paulo, 2007). Isaacson dedicates a full chapter to the issue “Einstein’s God”. In this chapter, the author reproduces declarations made by the father of the theory of relativity that allow to consider him a religious man (in a wide sense) and other declarations that turn him away from the Judaic-Christian belief in a personal God. Further ahead, the author quotes a paradoxal phrase of Einstein’s: “I’m a deeply religious non-believer.” (546).

The biographer lets Einstein himself speak: “Try and penetrate with our limited means the secrets of nature and you will find that behind all the discernible laws and connections, there remains something subtle, intangible and unexplainable. Veneration for this force beyond anything that we can comprehend is my religion. To that extent I am, in fact, religious” (p.394) “A scientists greatest satisfaction” is achieving the comprehension “that God himself could not have organized these connections in any other way than that in which it really exists, just as it isn’t within His power to make 4 a prime number” (p. 395).

“I’m not an atheist. The problem this conveys is far too vast for our limited minds. We are in the same situation as a small child who enters a library full of book in many languages. The child must now that someone wrote those books. He doesn’t know how nor does he understand the languages in which they were written. The child has a strong feeling that there is a mysterious order in the organization of the books, but doesn’t know what this is. It seems to me this is the attitude of human beings, even the most intelligent ones, in relation to God. We see a universe that is wonderfully organized and that obeys to certain laws, but we barely understand these laws” (p. 396)

In the conclusion of the small book titled The world as I see it (Nova York, 1949) known in Portuguese by the name No que eu acredito, Einstein wrote: “The fairest thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of true art and true science. He who knows it not and can no longer wonder, no longer feel amazement, is as good as dead, a snuffed-out candle. It was the experience of mystery-even if mixed with fear- that engendered religion. A knowledge of the existence of something we cannot penetrate, of the manifestations of the profoundest reason and the most radiant beauty, which are only accessible to our reason in their most elementary forms -it is this knowledge and this emotion that constitute the truly religious attitude; in this sense, and in this alone, I am a deeply religious man” (p. 397).

But on the question “Do you believe in God?”, Einstein answered: “I cannot conceive a personal God that has direct influence in the actions of the individuals or that judges the creatures of his own creation. My religiousness consists in the humble admiration of the infinitely superior spirit that reveals itself in what little we manage to understand about the world which can be known. This deeply emotional conviction of the presence of a rational superior power that reveals itself in this incomprehensible universe is my idea of God” (p. 398). In other occasions, the author of the theory of relativity described his concept of God: “I believe in Spinoza’s God who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists; not in a God who concerns himself with the fates and actions of human beings” (p. 399).

Dawkins quotes this last phrase and relativizes Einstein’s most religious declarations saying that “Einstein used ‘God’ in a purely metaphoric, poetic sense” (Deus – um delírio, p. 433). However, there is a clear contradiction between Dawkins and the biographer Isaacson. Let the reader be the judge: Dawkins declares that “(Einstein) was very often annoyed by the suggestion that he was a theist” (ib., p. 42). The biographer, on the contrary, says: “Einstein’s entire life was coherent when he refuted the accusation of being an atheist. ‘There are people who say that God does not exist’, he said to a friend. ‘But what angers me most is that they quote my name to support these ideas” (Isaacson, p. 399). “In fact, the biographer continues, Einstein used to be more critical towards those who ridiculed religion and who seemed to lack humility and the sense of amazement, than in relation to the faithful. ‘Fanatical atheists’ he explained in a letter ‘are like slaves who are still feeling the weight of their chains which they have thrown off after hard struggle. They are creatures who -in their grudge against traditional religion as the ‘opium of the masses’- cannot hear the music of the spheres” (ib., p. 400).

We conclude that militant atheists, like Dawkins, have no right to present Einstein as an ‘atheist scientist’. Einstein himself made a point of not being included among them. “What separates me from most so-called atheists is a feeling of utter humility toward the unattainable secrets of the harmony of the cosmos (…) You can call me an agnostic, but I do not share the crusading spirit of the professional atheist whose fervor is mostly due to a painful act of liberation from the fetters of religious indoctrination received in youth” (ib., p. 399-400). From our part, we acknowledge that the famous German scientists didn’t believe in the God of the Judaic-Christian revelation. No believer can pray to Einstein’s God. We shall continue to pray to the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, the God of the ancient prophets of Israel, the God of the psalmists, and above all, to the God of our Lord Jesus Christ, who Jesus of Nazareth taught us to call Abba (Father).

Einstein didn’t know the God of Jesus, although he declared to be “fascinated by the luminous figure of Nazarene” (Isaacson, p. 396), but we believe he searched for him when he looked for the sense of life in the laws that rule the Universe. As for ourselves, we cannot take pride of knowing the One whom the theologian Karl Rahner named as the “abyss of incomprehension”. Let us be thankful for the “God of silence” that gives us the freedom to believe in Him or deny his existence.

__________________

Luis González-Quevedo, S.J. Jesuit priest, member of the Centro de Espiritualidade Inaciana de Itaici. Editor of Itaici. Revista de Espiritualidade Inaciana. He is the author of Um sentido para a vida: Princípio e Fundamento. São Paulo: Edições Loyola, 2007 .